Another academic year is coming to a close, amidst an atmosphere of mutual respect and peaceful educational relationship among international music students.

Another academic year is coming to a close, amidst an atmosphere of mutual respect and peaceful educational relationship among international music students.

“When it comes to blockages and obstacles in the research process, we must distinguish between difficulties or obstacles that may arise in the course of the investigation for argumentative reasons and obstacles of a personal nature. The former are actually the easiest to solve because they are natural and inherent to the epistemology of scientific research: scientific research progresses through successive adaptations. In very rare cases, a research project ends with the achievement of all its objectives, and precisely those objectives that were set at the planning stage. And that’s a good thing, because it means that the researchers did not proceed blindly, but took into account the evidence they encountered along the way.

However, since problems can arise at any time, it is always a good idea for a research project to have both short-term and long-term goals: to analyze a problem, a difficulty, to break it down into parts, segments, steps to be tackled one by one. This is the right strategy to overcome blockages and obstacles of any kind and not to be paralyzed by the enormity of the problems.

On the other hand, difficulties of a personal nature are not to be underestimated and are becoming more and more frequent. Blockages or paralysis, even for long periods, can be due to insecurity, fear, feelings of inadequacy resulting from the constant confrontation and extreme competition in which research is carried out today. There is a level of ambition that is often excessive and disproportionate to the actual knowledge of researchers who, until proven otherwise, are at the beginning of their careers. On the other hand, there is an urge to compete, a true and proper agonism that is taken to the extreme in academic environments where evaluation is based on mere arithmetic calculations of the number of publications, the number of conference papers, and other criteria that are not qualitative but purely quantitative.

The motto “publish or perish” is a phrase of despair. Our watchwords should be: humility instead of ambition, gradualism instead of precociousness, slowness instead of haste, rigor instead of the frenetic rhythm imposed by the desire to meet the next deadline.

It is not surprising that, in predisposed individuals, the mixture of ambition and agonism can be fatal, leading to real psychological disorders such as anxiety, panic attacks and, in the most severe cases, paranoid forms such as the impostor syndrome, typical of those convinced that they are not up to their role, or the false victimization syndrome, typical of those convinced that they are being persecuted by their colleagues or supervisors and who see in every gesture a sign of persecution against which they believe they must defend themselves. It is therefore not uncommon for even the correction of a thesis by a supervisor or the rejection of an abstract for a conference to be experienced as moments of discrimination, mobbing, persecution, or worse.

The biggest problem is that even the most titled academics who may end up in a position of responsibility often have no expertise in these matters and no tools to decipher these behaviors, so they often react with blatant incompetence.”

Francesco Finocchiaro – Cristina Pascu, Musical Research: Trends, Methods, and Contemporary Challenges, 19 November 2024, National Academy of Music “Gheorghe Dima”, Cluj-Napoca

Die institutionalisierte Lüge ist das Wesen eines totalitären Regimes: eines Regimes, das nicht nur das Gedächtnis umformt und Informationen manipuliert, sondern durch die Neuschöpfung der Sprache das Kriterium der Wahrheit selbst zerstört. Der Staat, die Institution, oder auch die Akademie, die gewaltsam die These einer Minderheit über die Mehrheit stellt, handelt nach einer totalitären Logik: ein schonungsloses Vorgehen, eine mafiöse Macht, die kein anderes Grundgesetz kennt als das Führerprinzip.

The institutionalized lie is the essence of a totalitarian regime: a regime that not only reshapes memory and manipulates information, but also destroys the very criterion of truth by recreating language. The state, the institution or even the academy that violently places the thesis of a minority above the majority acts according to a totalitarian logic: a ruthless approach, a mafia-like power that knows no other constitutional law than the Führerprinzip.

Francesco Finocchiaro, Musik als Staatskunst in der nazifaschistischen Kulturpolitik, Annual Conference of the German Musicological Society, Hochschule für Musik und Tanz Köln, 11-14 September 2024

The notion of ‘source’ poses considerable problems for the study of silent film music. On the one hand, from a purely historical point of view, it is worth remembering that most of the music for the films of the silent era no longer exists. On the other hand, a vast repertoire of stock photoplay music has come down to us from the silent era, as an example of specialised publishing in the field of film music. Collections such as Kinothek, Motion Picture Moods, Filmharmonie, and many others consisted of original pieces that were not associated with a specific film but were designed to fit into standard narrative situations or to provide a common emotional aura. The practice of reusing and re-functionalising mood music pieces, constantly hovering between composition and compilation, raises philological questions concerning the multiple definition of the musical text, its author, and its performance. The score of a piece of stock photoplay music is not, in fact, the source of an opus in the strict sense of the term. It is not an aesthetically grounded entity, but rather an operational instruction at the service of a subsequent creative act: the one that will shape the musical accompaniment of a particular film screening in the cinema. The ubiquity of photoplay music is not the exception, but the rule. Indexing and cataloguing a source of stock photoplay music is not in itself useful historical knowledge if it is complemented by knowledge of its adaptive uses. These, however, are not to be found in the primary source, but must be reconstructed by consulting secondary sources of various kinds, from cue sheets to journalistic reviews, which only in their constellation give an account of the cinematic show as a whole.

Francesco Finocchiaro, Photoplay Music as Key Source for a New Historiographical Paradigm, «Fontes Artis Musicae», LXXI n. 2, April-June 2024, pp. 63-84.

„Es gibt Lebensmomente, die wie Grenzmarken vor eine abgelaufene Zeit sich stellen, aber zugleich auf eine neue Richtung mit Bestimmtheit hinweisen.

In solch einem Übergangspunkte fühlen wir uns gedrungen, mit dem Adlerauge des Gedankens das Vergangene und Gegenwärtige zu betrachten, um so zum Bewußtsein unserer wirklichen Stellung zu gelangen“.“There are moments in life that stand like boundary markers in front of a time that has passed, but at the same time they point with certainty in a new direction.

At such points of transition, we feel compelled to look at the past and present with the eagle eye of thought in order to become aware of our true position”.Karl Marx, Brief an den Vater, 1837

Das Habilitationsverfahren wurde an der Leopold-Franzens-Universität Innsbruck ordnungsgemäß durchgeführt. Ihre hervorragende wissenschaftliche Qualifikation ist auf Grund der Gutachten und Stellungnahmen nachgewiesen, Ihre didaktischen Fähigkeiten sind durch die mehrmalige Lerhtätigkeit an anerkannten postsekundären Bidlungseinrichtungen belegt. Die Voraussetzungen für die Erteilung der Lehrbefugnis sind somit erfüllt.

Innsbruck, am 4. Dezember 2023

Last 24 October 2023 marked the culmination of a journey of professional growth that began more than 10 years ago and was vigorously pursued despite the efforts of those who, between 2018 and 2020, did everything in their power to end my career.

After the evaluation of the Habilitationsschrift entitled Durch einen Gazeschleier. Ästhetik der Filmmusik in der Stummfilm-Ära, the Department of Musicology at the University of Innsbruck awarded me the Habilitation und venia legendi in Historische Musikwissenschaft.

The final event of the habilitation process was the lecture Paradigmen der Gegensätze. Als Musiker und Maler ins Kino gingen.

The newly designeted PD Dr. phil. Francesco Finocchiaro thanks the Evaluation Committee for their valuable suggestions and the Chairman of the Habilitation Committee, Univ.-Prof. Federico Celestini, for his rare professional and human care.

New doors will open and new experiences will begin. A new start in beautiful surroundings, with all comforts and facilities.

But all of this blessed beauty would be of no use without a sane relationship and an ethically based human environment.

In a well-known interview with Lotte Eisner titled Musikalische Illustration oder Filmmusik?, Kurt Weill declared his personal program of emancipation of film music from the age-old principle of ‘illustration’, that is, the subordinate role of the musical component to dramatic action. The accompanying music – he claimed – should not simply illustrate the events that take place onstage, but should have a “purely musical shaping”, a formal and structural integrity of its own.

After this reflection, he strongly criticized Edmund Meisel’s principle of Lautbarmachung: this idea of ‘acoustic manifestation of reality’, which had informed Meisel’s score for Potemkin (1926), would have never been able to provide “a solution to the problem of film music”. On the contrary, according to Weill this long-awaited solution was to be achieved through an “objective, almost concertante film music”. In film, just like in drama, music should be an independent component that stands in a dialectical relationship with the staged events, instead of sedulously illustrating them. Through this ‘concertante’ quality, music can become an essential part of the ‘epic attitude’ of the artwork. Through the tension that it establishes with the action or the visual sphere—for instance by providing an antiphrastic counterpoint to it, or by interrupting its flow—music unmasks the illusion of realism of the narrative fiction. ‘Concertante music’ prevents spectators from passively identifying with fiction, instead pushing them to actively search for nuances of meaning that hide behind outer behaviors.

The principle of ‘concertante music’ was widely applied not only in Weill’s musical theater, from the music for Dreigroschenoper to the opera buffa Aufstieg und Fall der Stadt Mahagonny, but also in many scores for cinema of the early 1930s-Germany by art-music composers and film-music specialists such as Paul Dessau, Hanns Eisler, Walter Gronostay and Weill himself. A thorough analysis of audiovisual montage casts light on a variety of dramaturgic choices, from dramaturgical counterpoint to horizontal collage, all of which share two basic features: the preservation of some degree of formal coherence for the musical component and the tendency to treat music and sound like any other montage material.

Overcoming any slavish illustration of the narrated events in favor of a type of music that is able to establish a dialectical tension with the stage events, and constitutes an autonomous text with its own formal coherence and semantic density, is the most important legacy cinema received from Weill’s principle of ‘concertante music’.

Francesco Finocchiaro, Kurt Weill and the Principle of ‘Concertante Music’, in The Works of Kurt Weill: Transformations and Reconfigurations in 20th-Century Music, edited by Naomi Graber and Marida Rizzuti, Turnhout, Brepols, 2023, pp. 21–36.

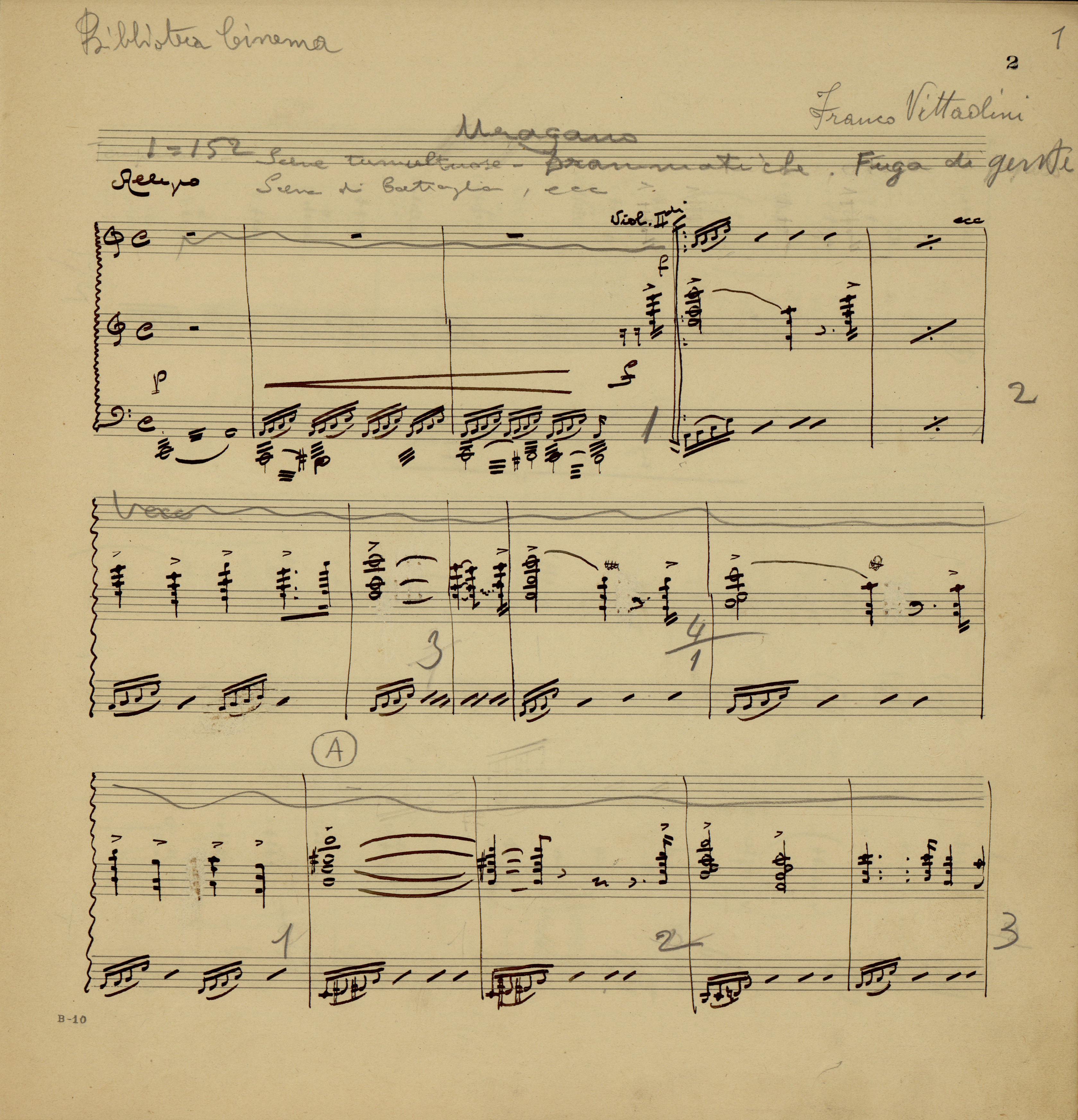

The notion of ‘musical source’ gives rise to considerable problems in the study of silent film music. On a purely historical level, it should be remembered that most of the music for silent films no longer exists. On the other hand, a vast repertoire of mood music from the silent era has come down to us as an example of specialised publishing in the field of film music. Collections such as Kinothek, Motion Picture Moods, Filmharmonie and many others consisted of original pieces that were not associated with a specific film, but were designed to fit into standard narrative situations or to provide a common emotional aura.

The practice of reusing and re-functionalising these pieces of music, constantly oscillating between composition and compilation, raises ontological problems concerning the multiple definition of the musical work, its author and its performance. The score of a piece of mood music is not, in fact, the source of an opus in the strict sense of the term. It is not an aesthetically grounded entity, but rather an operational instruction at the service of a subsequent creative act: the one that will shape the musical accompaniment of a particular film screening in the cinema.

The ubiquity of mood music is not the exception, but the rule. Identifying and cataloguing a piece of mood music is therefore not in itself a useful scholarly knowledge unless it is complemented by knowledge of its adaptive uses. These, however, are not to be found in the primary source, but must be reconstructed by consulting secondary sources of various kinds, from film scenarios to journalistic reviews, which only in their constellation give an account of the cinematic show as a whole.

Francesco Finocchiaro, Ontological Problems of Silent Film Music between Compilation and Composition, IAML Annual Meeting, University of Cambridge, 31 July – 4 August 2023.

A lecture on the pioneer of silent film music, Giuseppe Becce, and a round table on the current outlook for soundtracks marked the beginning of the professional collaboration with Lago Film Fest: a stimulating and joyful environment, immersed in a beautiful naturalistic setting, dedicated to promoting independent cinema and its professionals.

Lago Film Fest, Revine Lago (TV), July 21-29, 2023.

At the end of the 1920s, the German film giant Universum Film A.-G. (Ufa) established an industrial alliance with the Italian Istituto Nazionale Luce: signed in 1928, the agreement provided for the exchange of footages for the respective newsreels, within the framework of a consolidation of political-propaganda action in both the countries. The ‘pact of steel’ between Luce and Ufa was reaffirmed in 1933. In that year, Third Reich propaganda minister Joseph Goebbels went to Rome, where he met Luigi Freddi, then responsible for the propaganda of the Fascist regime, and explained to him the functioning of the Reichsfilmkammer. Goebbels’ criteria for the political reorganization of German cinematography were taken as a model by the Fascist intellectuals, so much so to be enthusiastically commented in the regime’s cultural journals.

The first result of the Luce-Ufa collaboration was the documentary Lo stormo atlantico (1931), dedicated to the transoceanic flight by a team of seaplanes headed by Italo Balbo. Shot by camera operator Mario Craveri, the film was sent to Germany to be synchronized with the Tobis-Klangfilm system. The soundtrack, upon which we well dwell for the purpose of this paper, was therefore edited independently in the Ufa studios.

The pact of steel between Fascist and Nazi cinematic industries consolidated at the outbreak of the World War II. There were two main areas of collaboration: (1) the co-production of documentary films on the progress of the war, between 1940 and 1941, and (2) the establishment of a newsreel, La Settimana Europea, the Italian translation of the Deutsche Wochenschau, during the Republic of Salò.

The Other ‘Pact of Steel’: The Luce-Ufa Cinematic Axis

Free paper at the International Conference “Music and Conflict: Politics and Escapism of Wartime Culture”.

Institute of Austrian and German Music Research

University of Surrey, 19-20 May 2023

You must be logged in to post a comment.